Hollow-pipe mining-claim markers were set up by prospectors during about 1970 to 1990 to mark the corners of their claims. Prior to that time, prospectors in the western deserts used piles of stones (cairns). As would be expected, looking for a pile of stones in the desert, which many people feel is "just a pile of stones anyways," can be difficult. Later, prospectors added 5-foot tall, 4x4-inch wooden posts to their cairns to make them more visible on the landscape, but wooden posts are heavy and awkward to haul around. With the availability of inexpensive PVC plastic pipes starting in the 1960s, 3- and 4-inch diameter, white PVC pipes became favored mining claim markers because they are light weight and visible from 3 miles away.

Figure 1. Stone cairn (left), and stone cairn with 4x4 wooden post (right), marking the corners of long forgotten mining claims in Gold Butte National Monument.

The 1970-1990 era coincided with a boom in speculative prospecting. It became a hobby for desert rats to head out with friends on the weekend and set up mining claims regardless of what minerals might, or might not, be found. A standard mining claim is 20 acres, and for $10/yr, a prospector could hold title to the minerals. Some prospectors salted their claims with gold and diamonds (Nevada is not a diamond producing state) to sell them to unsuspecting out-of-state investors. The speculative craze became so heated that in at least two cases, prospectors hired helicopters to fly over the landscape kicking mining claim markers out the door at appropriate intervals to mark off 20-acre claims. Although prospectors each filed paperwork with county officials attesting to their mineral discoveries, nobody ever checked. It was estimated that during these 20-years, some 1,000,000 hollow pipes were set up in the western states, with perhaps 600,000 in Nevada alone.

Figure 2. A perforated, hollow-pipe mining claim marker in Gold Butte. It is legal in Nevada to knock these markers down and leave them lying on the ground where they no longer pose a hazard to birds and other creatures.

By about 1980, however, wildlife biologists began raising the alarm because hollow pipes were found to inadvertently trap and kill birds and other small creatures. Some bird species, especially those that nest in old woodpecker holes and similar cavities, would hop down into the pipes to investigate "the cavity" as a place to nest -- never to return. The smooth inner walls of the pipes provided no grip for their claws, and the pipes were too narrow for the birds to spread their wings. Unable to escape, birds were left to starve or dehydrate. Other species also get into the pipes, including bats and chipmunks, and surprisingly — native bees by the thousands. Perforated leach-field pipes pose additional threats because the ground-level holes let small creatures fall into the bottom of the pipe. Many beetles, scorpions, lizards, and small snakes fall into oblivion.

Figure 3. Ash-throated Flycatcher, a fairly common, cavity-nesting bird in Gold Butte.

Figure 4. Mummified carcass of a Western Screech-Owl (left) and the skulls of two Ash-throated Flycatchers (right) found inside hollow-pipe mining claim markers.

By about 1990, the federal agencies had moved to protect native wildlife and banned the use of hollow pipes for mining claims on public lands. In 1993, Nevada passed a law banning the use of uncapped, hollow pipes within the state. In 2009, Nevada amended the law requiring prospectors to remove hollow pipes and replace them with wildlife-safe markers. The most common claim marker seen these days is a 2x2-inch, 4-ft tall wooden post. The 1993 law also permitted the public to knock down any hollow pipes remaining on public lands starting in 2011 because they are presumed to be abandoned. We are, however, required to leave the pipes lying in place to make it easier for another prospector to re-stake the claim without resurveying it.

Figure 5. Wooden, 2x2-inch wildlife friendly mining claim marker in Gold Butte.

In addition to requiring the removal of hollow-pipe mining-claim markers in Nevada, the new law also raised the price of a claim from $10/yr to over $100/yr (now $155/yr). This resulted in most prospectors walking away and abandoning their speculative claims.

State and federal agencies, in conjunction with environmental organizations (e.g., Audubon, Sierra Club) and mining corporations (e.g., Barrick Gold), removed tens of thousands of abandoned mining claim markers in Nevada. The BLM Southern Nevada District (essentially Clark County) set a goal for themselves of ridding the district of hollow-pipe markers by the end of 2016.

In late 2015, the BLM called a meeting of local conservation organizations to discuss the issue of abandoned, mining claim markers in the Gold Butte region. They explained that because of the 2014 Bunkerville Troubles, the BLM was at risk of missing their goal of clearing Clark County of abandoned mining claim markers by December 2016. They asked for the assistance of the conservation community. Without funds for the project, however, only Friends of Gold Butte (FOGB) picked up the project.

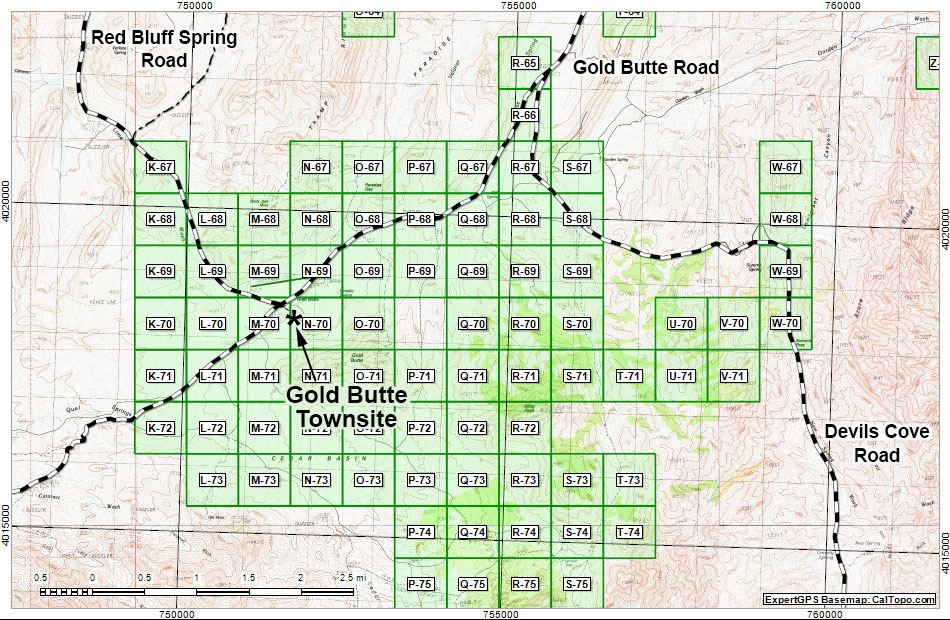

With only a year to clear the area, FOGB quickly jumped into action. We had already knocked down many markers, but a more systematic method was needed to ensure coverage of the entire area. Using maps provided by the BLM, we learned that mining claims had been recorded in 508 quarter-sections (a square area of land 1/2-mile on a side; 160 acres) of land in Gold Butte and 87 quarter-sections in the Logandale Trails area. While investigating these areas, we found another 40 quarter-sections to survey on the Mormon Mesa. With 635 quarter-sections to survey, which we came to refer to as "squares," we set to work.

Figure 6. Map of quarter-sections to be surveyed around Gold Butte Townsite, a small fraction of the 508 quarter-sections in Gold Butte.

Considerable effort was made to visit and survey each of the 635 squares. Some squares were easy; others were hard. By driving roads and hiking the old mining trails, FOGB crews could climb onto hilltops and use binoculars and spotting scopes to scan vast acreages of desert flats. In the mountains, however, FOGB crews spent hours climbing over ridges just to look over the other side. Using map-and-compass techniques, we made a map of the markers we'd seen.

With our map in hand, FOGB organized crews to hike out, locate, and knock down all of the markers in the area, and we learned: if you see one, you'll likely find more. We were very successful, and by keeping records, we were able to systematically sweep across Gold Butte, knocking pipes down. Sadly, we found astounding numbers of dead birds, mostly Ash-throated Flycatchers. Two pipes each contained 35 Ash-throated Flycatchers, but finding 4-6 per pipe was more common. We recorded Cactus Wrens, Rock Wrens, Northern Flickers, Ladder-backed Woodpeckers, European Starlings, House Finches, and others. We also recorded bats, white-tailed antelope squirrels, pocket mice, side-blotched lizards, western whiptail lizards, small snakes, beetles, tarantula hawks, butterflies, and thousands of native bees. We occasionally found live lizards, beetles, and scorpions to release, but perhaps the highlight was finding and releasing a live Ash-throated Flycatcher and seeing it fly off to it's mate.

Figure 7. FOGB mine-marker crew on a 2016 search-and-destroy mission during winter in Gold Butte.

Figure 8. It's usually easy to pull down a maker (left), but be sure to leave it in place (right).

During late December 2016, we celebrated the conclusion of the project on time and under budget with Gold Butte National Monument cleared of the scourge of hollow pipe mining claim markers. Or so we thought as the occasional marker turns up, but we had no idea what we'd find next …

Note: All distances, elevations, and other facts are approximate.

![]() ; Last updated 241019

; Last updated 241019

| Postcards | Trip Map | Copyright, Conditions, Disclaimer | Home |